Some unusual animal migrations

So, you’ve heard about Africa’s wildebeest making an annual loop around the Serengeti, and humpback whales migrating between their Antarctic feeding grounds and subtropical breeding grounds.

Are you aware, however, that the natural world includes a plethora of other, lesser-known spectacles involving large numbers of moving critters? Here’s where you can see eight of the world’s strangest migrations for yourself.

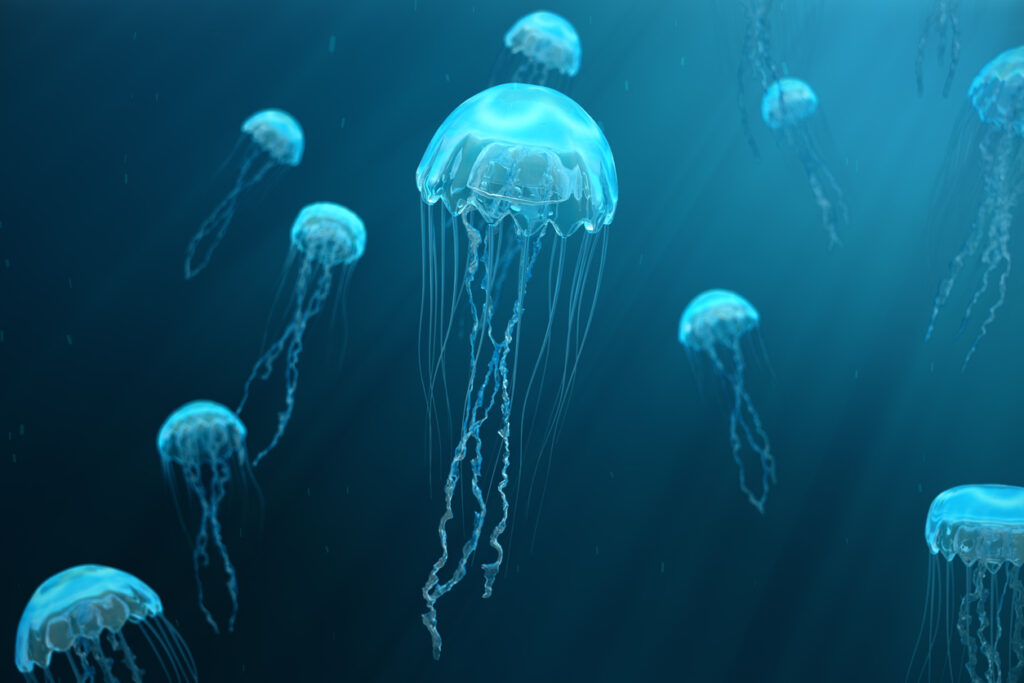

Golden jellyfish

Though jellyfish are notorious for floating around in ocean currents, the non-poisonous golden jellyfish of Palau’s famous Jellyfish Lake follow a special regular migration path that follows the sun’s arc through the sky. These soft-bodied animals congregate on the western shore of this Micronesian marine lake each morning to conduct a horizontal migration towards the rising sun, stopping just short of the shadows cast by the lakeside trees, where their primary predators, anemones, live. The jellyfish return in the early afternoon after taking a break when the sun is still high in the sky.

Monarch butterflies

Every September or October, millions of monarch butterflies migrate from their breeding grounds in southern Canada and eastern the United States to overwintering sites in central Mexico and California, where they huddle together in trees. These individual butterflies, unlike other species that make long migrations, will never return. Females may stop en route to lay eggs when the insects begin to flutter home again in May. The eggs hatch into striped caterpillars that eat a lot of milkweed before forming a chrysalis and transforming into adult butterflies after a few days.

Arctic terns

How far will you go to get away from the winter? For Arctic terns, this means leaving their summer breeding grounds in Greenland to travel all the way to the Weddell Sea on Antarctica’s coasts, then returning at the end of the Antarctic “summer” in what is known as the world’s longest migration path. The birds, which feed from the water while flying, don’t even fly straight, instead taking a 43,000-plus-mile (over 70,000-kilometer) S-shaped path both ways, equivalent to three journeys to the moon in a tern’s 34-year lifetime.

Spiny lobsters

These clawless crustaceans, which can be found all over the Caribbean, have one of the rarest undersea migrations. They form conga lines of up to 50 people and march offshore into deeper water across the ocean floor at the start of each season. In addition to escaping the summer storms that lash the Caribbean, egg-bearing females are thought to be able to encourage the production of their eggs by heading to cooler waters. When the autumn season comes, the lobsters return to shallower waters to breed. Although the reason for the lobsters forming a single line is unknown, some scientists believe the conga formation protects the arthropods from predators.